Showing posts sorted by relevance for query atheist philosophers. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query atheist philosophers. Sort by date Show all posts

Thursday, February 25, 2021

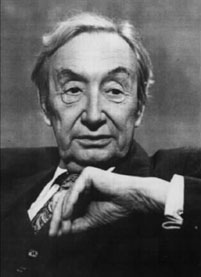

Smith and divine eternity

Quentin

Smith, one of the most formidable of contemporary atheist philosophers, died

late last year. One of the

reasons he was formidable is that he actually knew what he was talking about. Most of his fellow atheist philosophers do not,

as Smith himself lamented. In his

article “The

Metaphilosophy of Naturalism,” Smith opined that “the great majority

of naturalist philosophers have an unjustified belief that naturalism is true

and an unjustified belief that theism (or supernaturalism) is false.” He thought that most of them held their

opinion as a prejudice, and didn’t know or engage with the most serious

arguments of the other side. If that is

true even of most atheist philosophers, it is even more true of atheists

outside of philosophy – other secularist academics, New Atheist propagandists,

Reddit loudmouths, et al.

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Trust the experts

PhilPapers recently conducted a survey of opinion among academic philosophers, the results of which have been posted here. Here’s how all respondents from the survey’s “target faculty” answered when asked where they stand on the question of God’s existence:

ALL RESPONDENTS:

Accept or lean toward atheism 72.8%

Accept or lean toward theism 14.6%

Other 12.5%

And here’s how the results came out for respondents in two key subdisciplines:

RESPONDENTS SPECIALIZING IN PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION:

Accept or lean toward theism 72.3%

Accept or lean toward atheism 19.1%

Other 8.5%

RESPONDENTS SPECIALIZING IN MEDIEVAL AND RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY:

Accept or lean toward atheism 41.1%

Accept or lean toward theism 29.4%

Other 29.4%

Quite a difference. And regarding the last (Medieval/Renaissance) set of responses, it is worth pointing out that the fine-grained results show that “Other” includes a lot of agnostics, and that when the “lean towards” are excluded, atheism and theism are tied at 23.5% each, so that there are far fewer convinced atheists within this group than it might at first seem. It would also be nice to know what the results would have looked like if we separated out the medieval and renaissance specialists. (I would speculate that most Renaissance specialists approach their field out of interest in its relevance for understanding early modern philosophy rather than out of interest in medieval philosophy; and if so this is likely to reflect, on the part of Renaissance specialists, more familiarity with early modern philosophy than with medieval philosophy.) It seems very likely that the results for specialists in medieval philosophy specifically would have been more like those for specialists in philosophy of religion, especially for medieval specialists whose interest is in philosophy of religion related topics rather than in general metaphysics/epistemology, history of logic, etc.

Now, what do these results mean? You can be sure that some atheists will read the latter two sets of results as evidence only that many people who believe in God for non-philosophical reasons have flooded into philosophy of religion and medieval studies. And they will read the former results as evidence that philosophers who don’t enter the field with a religious ax to grind are more likely to be atheists.

But of course there is another obvious way to interpret the results in question – as clear evidence that those philosophers who have actually studied the arguments for theism in depth, and thus understand them the best – as philosophers of religion and medieval specialists naturally would – are far more likely to conclude that theism is true, or at least to be less certain that atheism is true, than other philosophers are. And if that’s what the experts on the subject think, then what the “all respondents” data shows is that most academic philosophers have a degree of confidence in atheism that is rationally unwarranted.

This dovetails with the judgment once made by the atheist philosopher Quentin Smith (in his paper “The Metaphilosophy of Naturalism”) to the effect that “the great majority of naturalist philosophers have an unjustified belief that naturalism is true and an unjustified belief that theism (or supernaturalism) is false.” And it also dovetails with the evidence we have examined in several earlier posts (e.g. here, here, and here) indicating that the more confident an atheist philosopher is that there are no good arguments for God’s existence, the more likely it is that he demonstrably does not know what the hell he is talking about.

In any event, it turns out that the people who are most likely to know what they are talking about on this subject tend overwhelmingly to believe in God, or at least (as in the combined medieval/renaissance results) to reject atheism. And as certain atheist philosophers like to insist, we should trust the experts, right?

ALL RESPONDENTS:

Accept or lean toward atheism 72.8%

Accept or lean toward theism 14.6%

Other 12.5%

And here’s how the results came out for respondents in two key subdisciplines:

RESPONDENTS SPECIALIZING IN PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION:

Accept or lean toward theism 72.3%

Accept or lean toward atheism 19.1%

Other 8.5%

RESPONDENTS SPECIALIZING IN MEDIEVAL AND RENAISSANCE PHILOSOPHY:

Accept or lean toward atheism 41.1%

Accept or lean toward theism 29.4%

Other 29.4%

Quite a difference. And regarding the last (Medieval/Renaissance) set of responses, it is worth pointing out that the fine-grained results show that “Other” includes a lot of agnostics, and that when the “lean towards” are excluded, atheism and theism are tied at 23.5% each, so that there are far fewer convinced atheists within this group than it might at first seem. It would also be nice to know what the results would have looked like if we separated out the medieval and renaissance specialists. (I would speculate that most Renaissance specialists approach their field out of interest in its relevance for understanding early modern philosophy rather than out of interest in medieval philosophy; and if so this is likely to reflect, on the part of Renaissance specialists, more familiarity with early modern philosophy than with medieval philosophy.) It seems very likely that the results for specialists in medieval philosophy specifically would have been more like those for specialists in philosophy of religion, especially for medieval specialists whose interest is in philosophy of religion related topics rather than in general metaphysics/epistemology, history of logic, etc.

Now, what do these results mean? You can be sure that some atheists will read the latter two sets of results as evidence only that many people who believe in God for non-philosophical reasons have flooded into philosophy of religion and medieval studies. And they will read the former results as evidence that philosophers who don’t enter the field with a religious ax to grind are more likely to be atheists.

But of course there is another obvious way to interpret the results in question – as clear evidence that those philosophers who have actually studied the arguments for theism in depth, and thus understand them the best – as philosophers of religion and medieval specialists naturally would – are far more likely to conclude that theism is true, or at least to be less certain that atheism is true, than other philosophers are. And if that’s what the experts on the subject think, then what the “all respondents” data shows is that most academic philosophers have a degree of confidence in atheism that is rationally unwarranted.

This dovetails with the judgment once made by the atheist philosopher Quentin Smith (in his paper “The Metaphilosophy of Naturalism”) to the effect that “the great majority of naturalist philosophers have an unjustified belief that naturalism is true and an unjustified belief that theism (or supernaturalism) is false.” And it also dovetails with the evidence we have examined in several earlier posts (e.g. here, here, and here) indicating that the more confident an atheist philosopher is that there are no good arguments for God’s existence, the more likely it is that he demonstrably does not know what the hell he is talking about.

In any event, it turns out that the people who are most likely to know what they are talking about on this subject tend overwhelmingly to believe in God, or at least (as in the combined medieval/renaissance results) to reject atheism. And as certain atheist philosophers like to insist, we should trust the experts, right?

Saturday, July 16, 2011

So you think you understand the cosmological argument?

Most people who comment on the cosmological argument demonstrably do not know what they are talking about. This includes all the prominent New Atheist writers. It very definitely includes most of the people who hang out in Jerry Coyne’s comboxes. It also includes most scientists. And it even includes many theologians and philosophers, or at least those who have not devoted much study to the issue. This may sound arrogant, but it is not. You might think I am saying “I, Edward Feser, have special knowledge about this subject that has somehow eluded everyone else.” But that is NOT what I am saying. The point has nothing to do with me. What I am saying is pretty much common knowledge among professional philosophers of religion (including atheist philosophers of religion), who – naturally, given the subject matter of their particular philosophical sub-discipline – are the people who know more about the cosmological argument than anyone else does.

In particular, I think that the vast majority of philosophers who have studied the argument in any depth – and again, that includes atheists as well as theists, though it does not include most philosophers outside the sub-discipline of philosophy of religion – would agree with the points I am about to make, or with most of them anyway. Of course, I do not mean that they would all agree with me that the argument is at the end of the day a convincing argument. I just mean that they would agree that most non-specialists who comment on it do not understand it, and that the reasons why people reject it are usually superficial and based on caricatures of the argument. Nor do I say that every single self-described philosopher of religion would agree with the points I am about to make. Like every other academic field, philosophy of religion has its share of hacks and mediocrities. But I am saying that the vast majority of philosophers of religion would agree, and again, that this includes the atheists among them as well as the theists.

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

An exchange with Keith Parsons, Part I

Prof. Keith Parsons and I will be

having an exchange to be moderated by Jeffery Jay Lowder of The Secular

Outpost. Prof. Parsons has initiated the

exchange with a

response to the first of four questions I put to him last week. What follows is a brief reply.

Keith, thank

you for your very gracious response. Like

Jeff Lowder, you raise the issue of the relative amounts of attention I and

other theistic philosophers pay to “New Atheist” writers like Dawkins, Harris,

et al. as opposed to the much more serious arguments of atheist philosophers

like Graham Oppy, Jordan Howard Sobel, and many others. Let me begin by reiterating what I

said last week in response to Jeff, namely that I have nothing but respect

for philosophers like the ones you cite and would never lump them in with

Dawkins and Co. And as I showed in my

response to Jeff, I have in fact publicly praised many of these writers many

times over the years for the intellectual seriousness of their work.

Saturday, October 16, 2010

Classical theism, atheism, and the Godfather trilogy

The history of philosophy is like The Godfather Trilogy. The Godfather is one of the best movies ever made. The Godfather Part II is at least as good, and in the view of many people, maybe even better. The Godfather Part III? Well, there is definitely some good stuff in it. And then there is Sofia Coppola’s acting, and the absurd helicopter scene, and the replacement of Robert Duvall’s character with George Hamilton’s.

The history of philosophy is like The Godfather Trilogy. The Godfather is one of the best movies ever made. The Godfather Part II is at least as good, and in the view of many people, maybe even better. The Godfather Part III? Well, there is definitely some good stuff in it. And then there is Sofia Coppola’s acting, and the absurd helicopter scene, and the replacement of Robert Duvall’s character with George Hamilton’s.Compare the ancient, medieval, and modern periods in the history of philosophy: The achievements of the Greek philosophers outshine anything the other pagans were able to accomplish. The great medievals built on, and (in the view of some of us) surpassed, those achievements. The moderns? Well, some of them are very clever; occasionally, they even have something to say which is both original and insightful. But for the most part, what’s new in their work isn’t true and what’s true isn’t new. What’s best about the best of them is mainly that they are effective critics of the worst of them.

Needless to say, that is not a judgment most of the moderns themselves share. But it’s a judgment I’ve defended at length in The Last Superstition, and it is relevant to what I’ve been saying in recent posts about classical theism and theistic personalism. Properly to understand and evaluate classical theism, one needs to have a fairly solid grounding in the ancient and medieval traditions in philosophy. And that is, unfortunately, something even contemporary philosophers tend not to have, let alone pop atheist writers like Richard Dawkins and Co.

Unless they are specialists in the history of philosophy, contemporary philosophers mostly read other contemporary philosophers. In grad school, their grounding in the history of their subject usually consists in a course or three on some historical figure, and it is usually early modern thinkers – especially Descartes, Hume, Kant, and Nietzsche – who are studied. Naturally, a course in Plato or Aristotle might be taken as well, but their metaphysical ideas are likely either to be treated as historical curiosities and veiled behind an impenetrable fog of caricature, or, when treated sympathetically, to be (mis)interpreted in a way that will make them conform to contemporary prejudices. (“Aristotle was a kind of functionalist!”) And for most grad students, the medievals are virtually invisible – a bunch of Catholics who may by accident have said something interesting here or there about logic or free will, but who have even less contemporary relevance than the ancients.

In short, the average contemporary philosopher is like the movie buff who has seen The Godfather Part III fifteen times, has seen a few scenes from The Godfather, though not the best parts, and has never seen The Godfather Part II at all, though he’s heard that a couple minutes of it might be OK. And on the basis of this, he judges that The Godfather Part III is obviously the best film in the series, that The Godfather has a few things going for it at least to the extent that it foreshadows Part III, and that The Godfather Part II isn’t worth bothering with. Needless to say, such a film buff wouldn’t even understand The Godfather Part III as well as he thinks he does, let alone the rest of the series; and most contemporary philosophers don’t understand even the modern period in philosophy as well as they think they do, let alone the centuries that preceded it.

To be sure, the contemporary atheist philosopher has usually read at least Aquinas’s Five Ways, but he also typically very badly misunderstands them, tearing them from their context and reading into them all sorts of modern assumptions that Aquinas would have rejected (as I show at length in Aquinas). You can find on YouTube all sorts of spoof trailers of famous movies “recut” to make them seem radically different – such as The Shining transformed into a romantic comedy, or Back to the Future remade in the image of Brokeback Mountain. The typical atheist commentator on the Five Ways is like the critic of The Godfather Part II who has seen only this YouTube goof assimilating Michael Corleone and Heath Ledger’s Joker.

More generally, judging theism exclusively on the basis of the work of theistic personalists like Paley, Swinburne, and Plantinga is (from a classical theist point of view, anyway) like judging The Godfather Trilogy as a whole on the basis of the best parts of The Godfather Part III alone. And judging theism on the basis of caricatures of theistic personalism – as New Atheist writers tend to do – is like judging the trilogy entirely on the basis of Sofia Coppola’s scenes in Part III. Nor does explaining this to New Atheist types ever seem to make a dent. The “Flying Spaghetti Monster” analogy, the “Courtier’s Reply” dodge, the “If everything has a cause, then what caused God?” canard – a certain kind of atheist is simply too much in love with these sleazy rhetorical moves ever to give them up. Just when you think you’re done with them, they pull you back in.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

Lowder then bombs

Atheist

blogger and Internet Infidels co-founder Jeffery Jay Lowder seems like a

reasonable enough fellow. But then, I

admit it’s hard not to like a guy who

writes:

I’ve just about finished reading

Feser’s book, The

Last Superstition: A Refutation of the New Atheism. I think Feser makes some hard-hitting, probably fatal, objections to the

arguments used by the “new atheists.”

Naturally

Lowder thinks there are better atheist arguments than those presented by the “New

Atheists,” but it’s no small thing for him to have made such an admission -- an

admission too few of his fellow atheist bloggers are willing to make, at least

in public. So, major points to Lowder

for intellectual honesty.

Saturday, April 4, 2009

Give me that old time atheism

Last night I was dipping into Roy Abraham Varghese’s Great Thinkers on Great Questions, an interesting collection of interviews with a number of prominent philosophers (including A. J. Ayer, G. E. M. Anscombe, Alvin Plantinga, Richard Swinburne, Ralph McInerny, Brian Leftow, Gerard Hughes, and many others) on topics mostly related in one way or another to religion. Some of Ayer’s remarks brought to mind how different earlier generations of agnostics and atheists had been, not merely culturally (as Roger Scruton has noted) but philosophically. Ayer, though a notorious lifelong foe of religion, was not a materialist. In his famous book Language, Truth, and Logic, he attempted (as he reminds us in the Varghese volume) to reduce physical objects to “sense-contents,” entities which were intended to be neutral between mind and matter but which were in fact (as Ayer admits) closer to the mental than to the physical side of the traditional mental/physical divide. Hence the resulting position was “much more nearly mentalistic than physicalistic.” And to the end of his life he apparently always rejected any attempt to reduce the mental to the physical.

Last night I was dipping into Roy Abraham Varghese’s Great Thinkers on Great Questions, an interesting collection of interviews with a number of prominent philosophers (including A. J. Ayer, G. E. M. Anscombe, Alvin Plantinga, Richard Swinburne, Ralph McInerny, Brian Leftow, Gerard Hughes, and many others) on topics mostly related in one way or another to religion. Some of Ayer’s remarks brought to mind how different earlier generations of agnostics and atheists had been, not merely culturally (as Roger Scruton has noted) but philosophically. Ayer, though a notorious lifelong foe of religion, was not a materialist. In his famous book Language, Truth, and Logic, he attempted (as he reminds us in the Varghese volume) to reduce physical objects to “sense-contents,” entities which were intended to be neutral between mind and matter but which were in fact (as Ayer admits) closer to the mental than to the physical side of the traditional mental/physical divide. Hence the resulting position was “much more nearly mentalistic than physicalistic.” And to the end of his life he apparently always rejected any attempt to reduce the mental to the physical.The reason for this is that even agnostic and atheist philosophers of Ayer’s generation generally recognized that materialism is just prima facie implausible. As I have noted in some earlier posts (here and here), and as I discuss at length in The Last Superstition, dualism was by no means a deviation from the broadly mechanistic conception of matter contemporary philosophy has inherited from the 17th century, but rather a natural consequence of that conception, given its highly abstract and mathematical redefinition of the material world. If matter is what the mechanistic view says it is, then (it seems) there is simply nowhere else to locate color, odor, taste, sound, etc. (as common sense understands these qualities, anyway), and nowhere else to locate meaning (given the banishment of final causes from the material world), than in something immaterial. And until about the 1960s, most philosophers (the occasional exception like Hobbes notwithstanding) seemed to realize that, short of returning to an Aristotelian hylemorphic philosophy of nature, the only plausible alternatives to dualism were views that tended to put the accent on mind rather than on matter – such as idealism, phenomenalism, or neutral monism.

The last of these, as its name implies, was officially committed to the view that the basic stuff out of which the world is constructed is “neutral” between mind and matter, but notoriously it tends to collapse into either phenomenalism or idealism. In my atheist days, it was the version of neutral monism developed by Bertrand Russell (or rather a riff on that version developed by F. A. Hayek) that I took to be the most plausible approach to the mind-body problem. (In recent philosophy, Russell’s views have been developed, in a way that seeks to avoid any sort of idealism, by Michael Lockwood; and, in a way that to some extent or other concedes their idealistic implications, by Galen Strawson and David Chalmers. In my Russellian days I was more attracted to Lockwood’s approach.) After a brief flirtation with materialism while an undergrad, I was more or less inoculated against it by John Searle’s writings, and came to regard the Russellian approach as the most plausible way to defend a naturalistic (if non-materialistic) view of the world.

Most naturalistic philosophers are not at all attracted to this approach, however, precisely (I would suggest) because of its tendency to collapse into some sort of philosophical idealism. For to make mind out to be the ultimate reality is – as the history of 19th century idealism shows – to adopt a view which must surely strike most naturalists as “too close for comfort” to a religious view of the world. To be sure, Chalmers and Strawson do not take their position in anything like a religious direction, but so far few other naturalists have been willing to follow them.

But if they were wise, they would do so. Chalmers and Strawson are in fact among the most interesting philosophers of mind writing today, in part because of their attempt to defend a kind of naturalism while acknowledging the very deep philosophical difficulties inherent in materialism. (Strawson famously dismisses materialism as “moonshine.”) As I have been lamenting in recent posts, most contemporary philosophical naturalists (to say nothing of non-philosophers who are naturalists, such as the New Atheists) have only the most crude understanding of the theological views they dismiss so contemptuously. In the same way, they tend also to be absurdly overconfident about the prospects of a materialist or physicalist account of the mind.

Earlier generations of philosophical atheists or agnostics – Ayer, Russell, Popper, to name just three – knew how difficult it is to defend such an account, and thus avoided grounding their atheism or agnosticism in a specifically materialist metaphysics. Some of their contemporary successors – Lockwood, Chalmers, Strawson, Nagel, Searle, Fodor, McGinn, Levine, among others – have, to varying degrees, some awareness of the same problems. Consequently, at least some of these people realize that naturalism itself (which seems most plausible precisely when spelled out in materialist terms) is by no means obviously right; it is something that requires a very great deal of effort to defend, and cannot blithely dismiss its rivals. Unfortunately, the bulk of contemporary philosophical naturalists – Dennett and Rey being by no means idiosyncratic in this regard – seem forever lost in their dogmatic slumbers.

ADDENDUM: I should note that Strawson does sometimes call his version of Russell's position "real materialism," and that Lockwood has occasionally said similar things. By contrast, Grover Maxwell, another Russellian who influenced both Lockwood and Strawson, repudiates any kind of "materialist" label even though his views are more or less identical to theirs. And Chalmers sometimes characterizes his own variation on Russellianism as a kind of "dualism"! So, the terminology here can get confusing. The point is that all of these authors reject materialism in the standard (Smart, Armstrong, early Putnam, Davidson, Dennett, Churchland, et al.) sense.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Some varieties of atheism

A religion typically has both practical and theoretical aspects. The former concern its moral teachings and rituals, the latter its metaphysical commitments and the way in which its practical teachings are systematically articulated. An atheist will naturally reject not only the theoretical aspects, but also the practical ones, at least to the extent that they presuppose the theoretical aspects. But different atheists will take different attitudes to each of the two aspects, ranging from respectful or even regretful disagreement to extreme hostility. And distinguishing these various possible attitudes can help us to understand how the New Atheism differs from earlier varieties.

Friday, December 13, 2013

Present perfect

Dale Tuggy has replied to my

remarks about his criticism of the classical theist position that God is

not merely “a being” alongside other beings but rather Being Itself. Dale

had alleged that “this is not a Christian view of God” and even amounts to “a

kind of atheism.” In response I pointed

out that in fact this conception of God is, historically, the majority position

among theistic philosophers in general and Christian philosophers in

particular. Dale replies:

Three

comments. First, some of [Feser’s] examples are ambiguous cases. Perfect Being

theology goes back to Plato, and some, while repeating Platonic standards about

God being “beyond being” and so on, seem to think of God as a great self. No

surprise there, of course, in the case of Bible readers. What’s interesting is

how they held – or thought they held – these beliefs consistently together.

Second, who cares who’s in the majority? Truth, I’m sure he’ll agree, is what

matters. Third, it is telling that Feser starts with Plato and ends with Scotus

and “a gazillion” Scholastics. Conspicuous by their absence are most of

the Greats from early modern philosophy. Convenient, because most of them hold,

with Descartes, that our concept of God is the “…idea of a Being who is

omniscient, omnipotent and absolutely perfect… which is absolutely necessary

and eternal.” (Principles

of Philosophy 14)

Sunday, April 10, 2016

Lofter is the best medicine

New Atheist

pamphleteer John Loftus is like a train wreck orchestrated by Zeno of Elea: As

Loftus rams headlong into the devastating objections of his critics, the chassis,

wheels, gears, and passenger body parts that are the contents of his mind proceed

through ever more thorough stages of pulverization. And yet somehow, the grisly disaster just

never stops. Loftus continues on at full

speed, tiny bits of metal and flesh reduced to even smaller bits, and those to

yet smaller ones, ad infinitum. You feel you ought to turn away in horror, but nevertheless find yourself settling

back, metaphysically transfixed and reaching for the Jiffy Pop.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Reading Rosenberg, Part I

I called attention in an earlier post to my review in First Things of Alex Rosenberg’s new book The Atheist’s Guide to Reality. Here I begin a series of posts devoted to examining Rosenberg’s book in more detail than I had space for in the review. The book is worthy of such attention because Rosenberg sees more clearly than any other prominent atheist just how extreme are the implications of the scientism on which modern atheists tend to base their position. Indeed, it is amazing how similar his conclusions are to those I argue follow from scientism in chapters 5 and 6 of The Last Superstition. The difference is that whereas I claim that these consequences constitute a reductio ad absurdum of the premises that lead to them, Rosenberg regards them as “pretty obvious” and “totally unavoidable” truths about an admittedly “rough reality,” which atheists should embrace despite its roughness. How rough is it? Writes Rosenberg:

Science -- especially physics and biology -- reveals that reality is completely different from what most people think. It’s not just different from what credulous religious believers think. Science reveals that reality is stranger than even many atheists recognize. (p. ix)

and

The right answers are ones that even some scientists have not been comfortable with and have sought to avoid or water down. (p. xii)

Friday, June 21, 2013

Mind and Cosmos roundup

My series of

posts on the critics of Thomas Nagel’s Mind

and Cosmos has gotten a fair amount of attention. Andrew Ferguson’s cover

story on Nagel in The Weekly Standard,

published when I was six posts into the series, kindly cited it as a “dazzling…

tour de force rebutting Nagel’s critics.”

Now that the series is over it seems worthwhile gathering together the

posts (along with some related materials) for easy future reference.

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Warburton on the First Cause argument

Bored while proctoring an exam today, I browsed through the desk drawer for something to read and found, among the other detritus of semesters past, a photocopy of the “God” chapter from Nigel Warburton’s Philosophy: The Basics, which some other professor had apparently once used for an Intro course. So I took a look. Several violent expletives later, the students had to ask me to quiet down so they could get back to distinguishing proximate genus from specific difference.

You won’t be surprised to learn that Warburton performs the usual ritual of criticizing the stupid “Everything has a cause etc.” version of the First Cause argument – a “version” which, of course, no one has ever actually defended. (Or, for you pedants out there, in case your Pastor Bob once taught it to you at Sunday school: a “version” which none of the many well-known philosophers who have endorsed the First Cause argument has ever actually defended.) That much would, perhaps, not be particularly noteworthy. This preposterous straw man litters both introductory philosophy textbooks and “New Atheist” pamphlets like the droppings stray neighborhood cats keep leaving on my lawn; and I have already declaimed upon the contemptible dishonesty of its use by pop atheists – and, most disgracefully, by many professional philosophers too – ad nauseam (e.g. here and here).

But Warburton ups the ante. Our man is not satisfied to leave his readers with the false impression that some actual theistic philosopher has ever argued “Everything has a cause; so the universe has an uncaused cause, namely God.” After all, a charitable reader might naturally, and quite rightly, think to respond: “Surely none of the defenders of this argument really said ‘everything’ – that would just be too obviously self-contradictory!” No, as if to forestall such a retort, Warburton assures us that “The First Cause Argument states that absolutely everything has been caused by something else prior to it,” that “The First Cause Argument begins with the assumption that every single thing was caused by something else,” and that the argument crucially assumes “that there can be no uncaused cause” (emphasis mine). Naturally, Warburton has no trouble “showing” that the defender of the First Cause Argument contradicts himself when he goes on to assert that God is an uncaused cause.

Strangely, Warburton provides no citations for this argument. Or not so strangely, since, as I have said, no defender of the First Cause argument has ever actually given it – not Plato, not Aristotle, not al-Ghazali, not Maimonides, not Aquinas, not Duns Scotus, not Leibniz, not Samuel Clarke, not Garrigou-Lagrange, not Mortimer Adler, not William Lane Craig, not Richard Swinburne, and not anyone else, as far as I know. Somehow, though, attacking this ridiculous caricature was judged by Warburton to be a more useful way of introducing his readers to the First Cause argument than presenting the actual views of any the great thinkers who’ve defended it. Wonder why.

Naturally too, Warburton also peddles the other standard myths about the First Cause argument. We are, for example, told matter-of-factly that “the argument presents no evidence whatsoever for a God who is either all-knowing or all-good.” Readers of The Last Superstition or Aquinas – or, more to the point, of the hundreds of pages written by the authors just mentioned arguing precisely for these and others among the divine attributes – know that this is what the kids today like to call “a blatant falsehood.” But again, this is something I’ve gone on about at length elsewhere (such as in the posts linked to above).

We are also told that what the argument seeks to rule out is “a never-ending series going back in time” – God as the knocker-down of the first domino, and all that. Never mind that most philosophers who have defended the argument – Aristotle, Aquinas, and Leibniz, to take perhaps the most significant figures – explicitly reject the strategy of arguing for a temporal first cause. And while there are other philosophers who have argued for a first cause of the beginning to the universe (most recently, William Lane Craig) Warburton entirely ignores their actual arguments as well.

So, what does Warburton’s discussion provide the beginning reader who is interested in learning about “the basics” (Warburton’s subtitle) of what philosophical theists have said about the First Cause argument? Nothing. Nothing whatsoever.

It will not do to suggest in his defense that Warburton only intended to show what was wrong with some crude arguments sometimes given by non-philosophers. For the title of his book is Philosophy: The Basics – not Crude Arguments Given By Non-Philosophers: The Basics.

Furthermore, when discussing some of the other traditional theistic arguments – the ontological argument and the design argument, for example – Warburton does attribute them to actual philosophers (Anselm and Descartes in the first case, Paley in the second). To be sure, his discussion is superficial here as well, but at least he is in these cases oversimplifying the actual arguments of these thinkers. By contrast, the purported “First Cause Argument” he criticizes bears no resemblance to anything a philosophical defender of the First Cause argument has actually said. That Warburton himself realizes this is evidenced by the fact that in this particular case, he does not even attempt to attribute the argument he is attacking to any actual philosopher.

So, why do a disgraceful number of professional philosophers – Warburton is hardly alone here – even bother with it? This too is a question I address in the first of the two posts linked to above. And it is hard to believe that the answer has anything to do with promoting a better public understanding of philosophy.

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Straw men and terracotta armies

Every academic philosopher solemnly teaches his students never to commit the straw man fallacy. And yet relentlessly committing it oneself anyway is almost a grand tradition within certain precincts of our discipline. As readers of The Last Superstition are aware, most of what the average contemporary secular philosopher thinks he “knows” about the traditional arguments of natural theology and natural law theory is nothing but a hodgepodge of ludicrous caricatures, and the standard “objections” to these arguments, widely considered fatal, in fact have no force whatsoever. If such philosophers’ continued employment depended on demonstrating some rudimentary knowledge of (for example) the actual views of Thomas Aquinas, many of them would be selling pencils.

Every academic philosopher solemnly teaches his students never to commit the straw man fallacy. And yet relentlessly committing it oneself anyway is almost a grand tradition within certain precincts of our discipline. As readers of The Last Superstition are aware, most of what the average contemporary secular philosopher thinks he “knows” about the traditional arguments of natural theology and natural law theory is nothing but a hodgepodge of ludicrous caricatures, and the standard “objections” to these arguments, widely considered fatal, in fact have no force whatsoever. If such philosophers’ continued employment depended on demonstrating some rudimentary knowledge of (for example) the actual views of Thomas Aquinas, many of them would be selling pencils.Consider this breathtaking example from an introductory book on philosophy:

The most important version of the first cause argument comes to us from Thomas Aquinas (1225-74).

The argument runs like this: everything that happens has a cause, and that cause itself has a cause, and that cause too has a cause, and so on and so on, back into the past, in a series that must either be finite or infinite. Now if the series is finite is [sic] must have had a starting point, which we may call the first cause. This first cause is God.

What if the series is infinite? Aquinas after some consideration eventually rejects the possibility that the world is infinitely old and had no beginning in time. Certainly the idea of time stretching backwards into the past forever is one which the human mind finds hard to grasp… Still we might note here that Aristotle found no difficulty in [this] idea. He held that the world has existed forever. Aristotle’s opinion, if correct, invalidates the first cause argument.

[From Jenny Teichman and Katherine C. Evans, Philosophy: A Beginner’s Guide, Second edition (Blackwell, 1995), p. 22.]

Now, I don’t need to tell you what’s wrong with this, right?

Maybe I do. Teichman and Evans are not liars, after all; they just don’t know any better. And if this is true of two professional philosophers, it’s bound to be true of many non-experts. Explaining everything that is wrong with this travesty of Aquinas would take several pages, and since you can find those pages in The Last Superstition, I direct the interested reader there. But very briefly: Aquinas nowhere in his case for God’s existence argues that the world had a beginning in time; indeed, he rather famously argues that it cannot be proved that it had such a beginning. Nor was he unfamiliar with Aristotle’s views on this subject, given that Aquinas was – again, rather famously – probably the greatest Aristotelian after Aristotle himself, and the author of many lengthy commentaries on The Philosopher’s works. What Aquinas seeks to show in all of his arguments for God’s existence is not the existence of a first cause who operated at some point in the distant past to get the world going, but rather one who is operating here and now, and at any moment at which the universe exists at all, to keep the world going. And part of his point is that the existence of such a God is something that can be proved even if the universe has always existed. (He did not actually believe it has always existed, mind you; he just didn’t get into the issue for the purposes of arguing for God’s existence.)

I don’t mean to pick on Teichman and Evans. Indeed, I have profited from some of Teichman’s work, and I enjoyed her occasional contributions to The New Criterion back when she was writing for them several years ago. But this is not a mere slip of the pen. This is a basic failure to make sure one knows what one is talking about before writing on something of major importance. The reason Teichman and Evans could get away with it is that so many other philosophers get away with it routinely, and no one calls them on it. (Here’s a set of errors, by the way – far more egregious and undeniable than any error allegedly made in the Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization – that Blackwell not only didn’t threaten to pulp the book over, but even left in the second edition!)

There are surely hundreds or even thousands of philosophers who think Aquinas is guilty of various fallacies because they simply don’t understand what his arguments are really about. And there are surely many more thousands of non-philosophers – including the students of the ignorant philosophers in question, and the readers of their works – who think the same thing. Widespread errors of this sort are an enormous part of the reason atheism has the respectability it has come to have. As I argue in TLS – indeed, as I claim to demonstrate there – atheism could not possibly have this status if most people who have an opinion on the traditional theistic arguments really knew what they were talking about. To be sure, there would still in that case be atheists (though far fewer of them); but they would know that the arguments on the other side are, at the very least, very challenging indeed.

The straw man argument is quite powerful, then – not logically, of course, but rhetorically. Indeed, it is especially powerful in the hands of philosophers, for unwary readers will naturally assume that a philosopher will be careful to have avoided fallacies, and will understand the philosophical ideas he is criticizing. Still, the traditional straw man has its limits. For there’s always the chance that someone will call attention to the real man. In the case of Aquinas, this has, thankfully, started to happen. Given the increase of interest in medieval philosophy over the last few decades, some awareness of what Aquinas really meant is starting, very slowly, to creep into the work of at least philosophers of religion who write on his arguments for God’s existence. It may take another decade or two, but we will hopefully get to the point where a passage like the one from Teichman and Evans wouldn’t pass the laugh test of any academic philosophy editor or referee anywhere, any more than would (say) a reference to Quine as a Thomist or to Nozick as a Marxist. And maybe a decade or two beyond that, the news will finally reach ignorant non-philosopher hacks like Richard Dawkins.

Even more powerful than this sort of straw man, however, is the sort that is not directed at any specific real man at all – a kind of free floating caricature of no one in particular, which can be associated or disassociated from particular targets as the rhetorical need of the moment calls for. Take what everyone “knows” to be the “basic” Cosmological Argument for God’s existence: Everything has a cause; so the universe has a cause, namely God. This argument is notoriously bad: If everything has a cause, then what caused God? And if God needn’t have had a cause, why must the universe have one? Etc. The thing is, not one of the best-known defenders of the Cosmological Argument in the history of philosophy ever gave this stupid argument. Not Plato, not Aristotle, not al-Ghazali, not Maimonides, not Aquinas, not Duns Scotus, not Leibniz, not Samuel Clarke, not Garrigou-Lagrange, not Mortimer Adler, not William Lane Craig, not Richard Swinburne. And, for that matter, not anyone else either, as far as I know. And yet it is constantly presented, not only by popular writers but also by professional philosophers, as if it were “the” “basic” version of the cosmological argument, and as if every other version were essentially just a variation on it.

Don’t believe me? Of course you do. Anyone who has ever taken a PHIL 101 course has heard this argument triumphantly refuted and quickly brushed aside so that the instructor could move on to the “philosophically serious” stuff.

In case there are any doubters, though, let’s look at a few examples. Here’s one from a New Atheist doorstop-sized pamphlet:

The Cosmological Argument… in its simplest form states that since everything must have a cause the universe must have a cause – namely God… [But then] what caused God? The reply that God is self-caused (somehow) then raises the rebuttal: If something can be self-caused, why can’t the universe as a whole be the thing that is self-caused?

[From Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (Viking, 2006), p. 242.]

“Well, come on,” you’re thinking, “that’s cheating. It’s Dennett! What did you expect, intellectual honesty and competence vis-à-vis religion?”

OK, then, here’s another one, from an introductory text on the philosophy of religion, no less:

The basic cosmological argument

1. Anything that exists has a cause of its existence.

2. Nothing can be the cause of its own existence.

3. The universe exists.

Therefore: The universe has a cause of its existence which lies outside the universe.

[From Robin Le Poidevin, Arguing for Atheism: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion (Routledge, 1996), p. 4]

Curious title, that. Imagine a book called Arguing for Conservatism: An Introduction to Political Philosophy. Think Routledge would publish it? Me neither.

But precisely for that reason, some might think that this example too is unrepresentative. The guy’s writing a book to promote atheism, after all, even if (unlike Dennett) he actually knows something about philosophy of religion. So here’s one further example, from a book on logic, a subject one would think is as objective and free of partisanship as is humanly possible:

It’s a natural assumption that nothing happens without an explanation: people don’t get ill for no reason; cars don’t break down without a fault. Everything, then, has a cause. But what could the cause of everything be? Obviously, it can’t be anything physical, like a person; or even something like the Big Bang of cosmology. Such things must themselves have causes. So it must be something metaphysical. God is the obvious candidate.

2. Nothing can be the cause of its own existence.

3. The universe exists.

Therefore: The universe has a cause of its existence which lies outside the universe.

[From Robin Le Poidevin, Arguing for Atheism: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion (Routledge, 1996), p. 4]

Curious title, that. Imagine a book called Arguing for Conservatism: An Introduction to Political Philosophy. Think Routledge would publish it? Me neither.

But precisely for that reason, some might think that this example too is unrepresentative. The guy’s writing a book to promote atheism, after all, even if (unlike Dennett) he actually knows something about philosophy of religion. So here’s one further example, from a book on logic, a subject one would think is as objective and free of partisanship as is humanly possible:

It’s a natural assumption that nothing happens without an explanation: people don’t get ill for no reason; cars don’t break down without a fault. Everything, then, has a cause. But what could the cause of everything be? Obviously, it can’t be anything physical, like a person; or even something like the Big Bang of cosmology. Such things must themselves have causes. So it must be something metaphysical. God is the obvious candidate.

This is one version of an argument for the existence of God, often called the Cosmological Argument.

[From Graham Priest, Logic: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2000), at pp. 21-2.]

Examples could easily be multiplied. A cursory inspection of the bookshelves here in my study turns up Michael Martin’s Atheism: A Philosophical Justification, Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian, and Simon Blackburn’s Think as further examples of books earnestly presenting the “Everything has a cause” argument as if it were something that actual philosophical advocates of the Cosmological Argument have historically defended.

(Blackburn, incidentally, has made the attacking of straw men something of a second career. In a review of a book of essays by Elizabeth Anscombe some years back, he peddled some stale caricatures of natural law theory. In his book on Plato’s Republic, he throws in several gratuitous, and indeed bizarre, references to neo-conservatives as disciples of Thrasymachus and advocates of cynical “realpolitik” – perhaps less a straw man than an outright smear, since the usual caricature of neo-conservatives paints them as naïve Wilsonian democratic idealists. Anyway, if Blackburn is looking for some imperative to use as a title for a sequel to Think, he might consider something like Repeat Clichés Fashionable Among Liberal Academics.)

The obvious “So what caused God, then?” rejoinder is usually made next (as in Dennett), though sometimes some other obvious objection is raised. For example, Martin asks “How do we know the first cause is God?” Slightly more creatively, Priest suggests that the argument commits a quantifier shift fallacy. (Even if everything does have a cause it does not follow that there is something that is the cause of everything.)

Now some of these writers go on to acknowledge that there are other and more sophisticated forms of the argument. In fact, Le Poidevin even admits that “no-one has defended a cosmological argument of precisely this form” (!) So why bother with it?

Well, here’s one possibility: Because, though shooting this fish in its barrel accomplishes exactly zip logically speaking, rhetorically the atheist’s battle against the Cosmological Argument is half-won by the time the unwary reader moves on to the next chapter. By effectively insinuating that the argument’s defenders must surely be a pretty stupid or at least intellectually dishonest bunch, anything you represent them as saying afterward, no matter how intrinsically interesting or philosophically powerful, is bound to seem anticlimactic, a desperate attempt at patching the gigantic holes in a pathetically weak case. Dennett, admitting that there are more sophisticated versions of the argument, suggests that only those with a taste for “ingenious nitpicking about the meaning of ‘cause’” and “the niceties of scholastic logic” would find them of any interest. Why waste time addressing them, then? And so he doesn’t. What the greatest defenders of the Cosmological Argument have actually said doesn’t matter. Poking holes in an argument that “no-one has defended” is enough to refute them.

As I have said, this is more effective than the usual “straw man” argument precisely because there is no “real man” being criticized. It isn’t strictly a distortion of anything any specific philosopher has actually defended. If you say “Hey, Aquinas [or Aristotle, Leibniz, or Maimonides, or whomever] never said anything like that!” the atheist can always reply “I never said he did – no straw man fallacy here! I’m just talking about, you know, the Cosmological Argument in general.” And yet somehow, the mud still sticks to Aquinas, Leibniz, Maimonides, and Co. anyway. It’s as if, in place of a single straw man, the atheist has constructed an entire field filled with straw men, in one fell swoop. Or, to shift analogies, instead of attacking the formidable Cosmological Argument army made up of the philosophical giants listed above, the atheist has decided to take on instead a clay or terracotta army of the sort the first Chinese emperor had buried with him. His “victory” is hollow, but since most readers wouldn’t know the real army from the clay one, it seems very real indeed.

If you’re a secularist reader having trouble working up much outrage over this, consider the following analogy. Suppose some conservative suggested in a book called Arguing for Chastity: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Sex that the following is “the basic argument” for the moral legitimacy of homosexual acts:

1. All sexual activity is good.

2. Homosexual acts are a kind of sexual activity.

3. So homosexual acts are good.

Suppose he then went on to point out that this is a terrible argument, that it would justify rape, adultery, child molestation, etc. And suppose further that he also acknowledged that “no-one has defended an argument of precisely this form” but claimed that it was somehow nevertheless a good starting point from which to assess the morality of homosexual acts, giving the impression that everything else actual liberals have ever said about the subject was essentially a desperate attempt to patch up this feeble argument.

I submit that any defender of liberal views about sex would consider this an outrage. And rightly so. But the way a great many philosophers present arguments like the Cosmological Argument is not one whit less outrageous.

And yet generations of philosophers have been formed in their thinking about religion by works taking this sort of dishonest (or at least woefully uninformed) rhetorical approach, not only where the Cosmological Argument is concerned (this is just one example) but also where other arguments for religion are concerned, and where arguments for traditional views about sex are concerned too, for that matter. The result is that lots of people who think they more or less know what the basic arguments are vis-à-vis these subjects know nothing of the kind. And as one of their number likes to say, the less they know, the less they know it.

2. Homosexual acts are a kind of sexual activity.

3. So homosexual acts are good.

Suppose he then went on to point out that this is a terrible argument, that it would justify rape, adultery, child molestation, etc. And suppose further that he also acknowledged that “no-one has defended an argument of precisely this form” but claimed that it was somehow nevertheless a good starting point from which to assess the morality of homosexual acts, giving the impression that everything else actual liberals have ever said about the subject was essentially a desperate attempt to patch up this feeble argument.

I submit that any defender of liberal views about sex would consider this an outrage. And rightly so. But the way a great many philosophers present arguments like the Cosmological Argument is not one whit less outrageous.

And yet generations of philosophers have been formed in their thinking about religion by works taking this sort of dishonest (or at least woefully uninformed) rhetorical approach, not only where the Cosmological Argument is concerned (this is just one example) but also where other arguments for religion are concerned, and where arguments for traditional views about sex are concerned too, for that matter. The result is that lots of people who think they more or less know what the basic arguments are vis-à-vis these subjects know nothing of the kind. And as one of their number likes to say, the less they know, the less they know it.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Churchland on dualism, Part I

We have been hammering away at eliminative materialism (EM) in a series of posts. If EM proponents fail to make their own position plausible or even coherent, how do they fare as critics of alternative views? Not much better. Let’s look at Paul Churchland’s treatment of dualism in (the 1988 revised edition of) his textbook Matter and Consciousness. (There’s the book’s cover at left. It’s better than the book itself, which I guess confirms the old adage. I considered using this illustration, but it seemed a bit impolite.)

We have been hammering away at eliminative materialism (EM) in a series of posts. If EM proponents fail to make their own position plausible or even coherent, how do they fare as critics of alternative views? Not much better. Let’s look at Paul Churchland’s treatment of dualism in (the 1988 revised edition of) his textbook Matter and Consciousness. (There’s the book’s cover at left. It’s better than the book itself, which I guess confirms the old adage. I considered using this illustration, but it seemed a bit impolite.)There are two main problems with Churchland’s discussion. First, his summary of the case for dualism is no good. Second, his arguments against dualism are no good either. In this post we’ll look at the first problem and in a second post I’ll address the second.

What are the main arguments for dualism? Churchland identifies four; he calls them the argument from religion, the argument from introspection, the argument from irreducibility, and the argument from parapsychology. To anyone familiar with the philosophical literature on dualism, this list cannot fail to seem very odd.

One problem with it is that it includes two arguments – the “argument from religion” and the “argument from parapsychology” – that dualist philosophers actually put little or no emphasis on. As Churchland presents the “argument from religion,” it amounts to little more than the claim that “Dualism must be true, because my religion says it is.” He cites no philosophers as actually having given this argument, no doubt because there aren’t any. (Yes, a philosopher who happens to believe on independent grounds that his religion is true and that it entails dualism might present that as an argument for dualism to someone who already agrees with its premises. But no dualist philosopher I can think of has ever pretended that such an argument would be a good stand-alone argument for convincing either an irreligious materialist or even someone whose attitude toward either religion or dualism is noncommittal.)

The “argument from parapsychology” no doubt does have some defenders; certainly there are serious philosophers who have taken the subject of alleged paranormal phenomena seriously either in a sympathetic way (e.g. C. D. Broad and, in recent years, Stephen Braude) or in a critical spirit (e.g. Antony Flew). But this subject does not in fact play much of a role in contemporary debates over dualism, and even those philosophers who believe that at least some purported paranormal phenomena cannot plausibly be explained away in terms of existing scientific theory (e.g. Braude) do not necessarily put such claims forward, primarily or at all, as grounds for accepting dualism.

It is in any event a mistake to think that dualism is intended as a kind of scientific hypothesis put forward as the “best explanation” of the empirical evidence, parapsychological or otherwise. The central arguments for dualism have always been attempts at metaphysical demonstration, intended to show conclusively that whatever the mind is, it cannot even in principle be material. And this brings us to the most glaring fault with Churchland’s list: He simply ignores these key arguments entirely. For example, though he purports to summarize Descartes’ own reasons for endorsing dualism, and rightly notes that Descartes thought that certain key mental phenomena are irreducible to material phenomena, he fails even to mention the two arguments Descartes put the most emphasis on: the clear and distinct ideas argument (these days often called the conceivability argument or the modal argument), and the indivisibility argument (which is related to what is often called the unity of consciousness argument). The first argument (which I have discussed in a previous post) holds that since – the argument claims – it is metaphysically possible for mind to exist apart from anything material, it cannot be material. The second holds that the mind has a kind of unity or indivisibility-in-principle that nothing material can have. (Variations on this basic idea were also defended by the likes of Leibniz and Kant.)

It isn’t like these arguments are not well known. Nor are they mere historical relics; they have defenders to this day. (For those who are interested, I discuss them in detail in my book Philosophy of Mind.) The modal argument in particular received renewed attention in the wake of Kripke’s Naming and Necessity, and thus in the years leading up to the publication of Churchland’s book. It was defended by Richard Swinburne in The Evolution of the Soul, which appeared in 1986 – two years before Churchland’s revised edition – and by W. D. Hart in The Engines of the Soul, which itself came out in 1988. (Charles Taliaferro is another philosopher who has defended it in the years since, in his book Consciousness and the Mind of God.)

Churchland also ignores – as, in fairness, almost all contemporary philosophers of mind do – what early modern writers like Malebranche regarded as the central proof of dualism, viz. that dualism follows from the very mechanistic conception of matter Cartesians and materialists hold in common. For if color, odor, taste, sound, etc., as common sense understands them, do not exist in matter itself but only in our perceptual experience of matter, then those experiences cannot be material. (I have discussed this argument in previous posts as well, e.g. here and here.)

What is in fact the chief argument for dualism, at least from the point of view of the classical (Platonic-Aristotelian-Thomistic-Scholastic) traditions in philosophy, concerns, not sensory qualities or “qualia,” but rather our capacity for abstract thought. For concepts, and our thoughts about them, are universal in a way nothing material can be, and (sometimes, anyway) determinate, precise, or unambiguous in a way nothing material can be. (I have discussed this sort of argument too in many earlier posts, e.g. here and here.) While this line of argument has also been largely ignored by contemporary academic philosophers of mind, it was defended by Mortimer Adler in the years leading up to the publication of Churchland’s book, and by 20th century Thomist writers generally. Needless to say, Churchland ignores it as well.

So, while Churchland pretends to be summing up “some of the main considerations” usually given in support of dualism, he completely ignores the arguments the most prominent dualist philosophers actually regarded as the most important, and includes arguments that dualists do not typically make use of – arguments that are either clearly feeble (the “argument from religion,” as Churchland presents it) or which rest on premises which are as controversial as dualism itself is (the “argument from parapsychology”). The rhetorical effect is obvious: The unwary reader, who assumes that a textbook will give him an accurate summary of what each side has to say, is bound to come away with a completely distorted conception of the case for dualism. In particular, he is bound to think it far weaker than it actually is.

I am not claiming that Churchland is knowingly perpetrating what looks like a pretty sleazy rhetorical tactic. I think he is, like most materialists, simply ignorant of what most dualists have actually said. He no doubt thinks he knows enough about what they say to be justified in concluding that their position is not worth looking into any further than he already has. He is wrong, but will never know that he is, because he has gotten himself onto the sort of merry-go-round that (as we have seen in recent posts) naturalists seem to have so much difficulty keeping off of: “I know that dualism is too silly to investigate any further because of how bad the arguments for it are; and I know that I must be understanding those arguments correctly because dualism is obviously just too silly to be worth investigating any further.”

The thing is, books like Matter and Consciousness contribute to the formation of the same mindset in others. As generation after generation of philosophy students are taught out of such books, the conclusion that dualism is intellectually disreputable comes to seem something that “everyone knows.” In fact, what “everyone knows” is nothing more than a bunch of straw men and circular arguments, bounced around the materialist echo chamber long enough that no one can hear anything else. (This is, of course, exactly parallel to what most atheist philosophers “know” about the classical arguments for God’s existence, as I have noted here, here, and here. The hegemony of atheism and materialism crucially depend on a stubborn and studied ignorance of what theists and dualists have actually said.)

Having said all that, Churchland is at least correct to say that what he calls the "argument from introspection" and the "argument from irreducibility" are prominent arguments for dualism. Unfortunately, what he says about these arguments is no good either. We’ll see why in part II.

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

Rosenberg roundup

Having now

completed our ten-part series of posts on Alex Rosenberg’s The

Atheist’s Guide to Reality, it seems a roundup of sorts is in

order. As I have said, Rosenberg’s book

is worthy of attention because he sees more clearly than most other contemporary

atheist writers do the true implications of the scientism on which their

position is founded. And interestingly enough,

the implications he says it has are more or less the very implications I argued scientism has in my own book The

Last Superstition. The

difference between us is this: Rosenberg acknowledges that the implications in

question are utterly bizarre, but maintains that they must be accepted because

the case for the scientism that entails them is ironclad. I maintain that Rosenberg’s case for

scientism is completely worthless, and that the implications of scientism are

not merely bizarre but utterly incoherent and constitute a reductio ad absurdum of the premises that lead to them.

Friday, October 16, 2015

Repressed knowledge of God?

Christian

apologist Greg Koukl, appealing to Romans 1:18-20, says

that the atheist is “denying the obvious, aggressively pushing down the

evidence, to turn his head the other way, in order to deny the existence of

God.” For the “evidence of God is so

obvious” from the existence and nature of the world that “you’ve got to work at

keeping it down,” in a way comparable to “trying to hold a beach ball

underwater.” Koukl’s fellow Christian

apologist Randal Rauser begs

to differ. He suggests that if a

child whose family had just been massacred doubted God, then to be consistent,

Koukl would -- absurdly -- have to regard this as a rebellious denial of the

obvious. Meanwhile, atheist Jeffery Jay

Lowder agrees

with Rauser and holds that Koukl’s position amounts to a mere “prejudice”

against atheists. What should we think

of all this?

Friday, October 23, 2015

Repressed knowledge of God? Part II

We’ve been

discussing the thesis that human beings have a natural inclination toward

theism, and that atheism, accordingly, involves a suppression of this

inclination. Greg

Koukl takes the inclination to be so powerful that resisting it is like “trying

to hold a beach ball underwater,” and appears to think that every single atheist

is engaged in an intellectually dishonest exercise in “denying the obvious, aggressively

pushing down the evidence, to turn his head the other way.” (Randal Rauser, who

has also been critical of Koukl, calls this the “Rebellion Thesis.”) In

response to Koukl, I argued that the inclination is weaker than that, that

the natural knowledge of God of which most people are capable is only “general

and confused” (as Aquinas put it), and that not all atheism stems from

intellectual dishonesty. Koukl has

now replied, defending his position as more “faithful to Paul’s words” in Romans 1:18-20 than mine is. However, I don’t think this claim can survive

a careful reading of that passage.

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

Dude, where’s my Being?

It must be

Kick-a-Neo-Scholastic week. Thomas

Cothran calls

us Nietzscheans and now my old grad school buddy Dale Tuggy implicitly labels us atheists. More precisely, commenting on the view that “God is not a being, one among others…

[but rather] Being Itself,” Dale opines that “this is not a Christian view

of God, and isn’t even any sort of monotheism. In fact, this type of view has always competed

with the monotheisms.” Indeed, he

indicates that “this type of view – and I say this not to abuse, but

only to describe – is a kind of atheism.” (Emphasis in the

original.)

Atheism?

Really? What is this, The Twilight Zone? No, it’s a bad Ashton Kutcher movie (if

you’ll pardon the redundancy), with metaphysical amnesia replacing the

drug-induced kind -- Heidegger’s “forgetfulness of Being” meets Dude, Where’s My Car?

Friday, October 21, 2011

Magic versus metaphysics

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Arthur C. Clarke

Any sufficiently rigorously defined magic is indistinguishable from technology.

Larry Niven

Some atheists are intellectually serious. Some are not. There are several infallible marks by which an atheist might show himself to be intellectually unserious. Thinking “What caused God?” is a good objection to the cosmological argument is one. Being impressed by the “one god further” objection is another. A third is the suggestion that theism entails a belief in “magical beings.” Anyone who says this either doesn’t know what theism is or doesn’t know what magic is. Or (no less likely) doesn’t much care one way or the other – it’s another handy straw man, useful for those who want to believe that theistic arguments are manifestly fallacious or otherwise silly, or who find it rhetorically useful to pretend that they are.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)