Philip Goff has kindly replied to my recent post criticizing the panpsychism he defends in his book Galileo’s Error and elsewhere. Goff begins by reminding the reader that he and I agree that the mathematized conception of nature that Galileo and his successors introduced into modern physics does not capture all there is to the material world. But beyond that we differ profoundly. Goff writes:

I agree with Galileo (ironic, given the title of my book) that the qualities aren’t really out there in the world but exist only in consciousness. So I don’t think we need to account for the redness of the rose any more than we need to account for the Loch Ness monster (neither exist!); but we do need to account for the redness in my experience. Following Russell and Eddington I do this by incorporating the qualities of experience into the intrinsic nature of matter, ultimately leading me to a panpsychist theory of reality.

End

quote. Now, as I noted in my earlier

post, this combination of views is odd right out of the gate. It starts out accepting the view that sensory

qualities aren’t really there in matter.

But then, noting the problems this raises, it proposes that the solution

is to hold that sensory qualities… really are

there in matter after all! Only, not in

the way we thought they were, but instead in some totally bizarre way that

creates further problems without solving any (which is indeed what Goff’s view

does, as I’ll show below).

This is

comparable to thinking about killing someone, and then, noting how problematic

this would be, proposing that after the murder we look for some way to resuscitate

the corpse, Frankenstein-style. All despite

the fact that this will leave us with a grotesque patchwork of a human being

rather than the original person! How about just not killing him in the first

place? Similarly, if you are going

to end up having to put the sensory qualities back into matter after all, why

not just refrain from taking them out?

Goff thinks

he has a positive argument for taking them out, which I’ll come to in a

moment. But first let’s note what he

says is the problem with not taking

them out:

Feser, in contrast, rejects Galileo’s

initial move of taking the qualities out of the external world. The redness

really is in the rose, the greenness really in the grass, etc., and hence we

have a ‘hard problem’ not just about consciousness but also about the qualities

in external objects.

End

quote. This is the reverse of the truth,

and Goff misses the point that rejecting Galileo’s move leaves us, not with a second “hard problem,” but rather with no “hard problems” at all. And Goff himself should see this, given his

other commitments. The so-called “hard

problem of consciousness” arises only if we assume that higher-level properties

must be reducible to lower-level ones

– that the qualitative character of a visual experience, for example, must be

reducible to neurological properties or the like. There will be a corresponding “hard problem”

of explaining how redness can be a feature of a rose only if we assume that

redness must be entirely reducible to properties of the sort described by

physics and chemistry.

But these

“problems” disappear if we reject this reductionist assumption. And Goff

himself rejects it, as I noted in my earlier post! He denies that all the higher-level

properties of a thing must be reducible to lower-level ones. So how can he justify the claim that

rejecting Galileo’s move would leave us with two “hard problems”? Indeed, how can he justify the claim that

accepting Galileo’s move would leave us with even one “hard problem” that calls for the radical solution of

panpsychism? Goff’s own commitments dissolve the problem, leaving the

panpsychist “solution” otiose even if it didn’t have its other defects.

Let’s turn

now to the positive argument Goff offers for accepting Galileo’s removal of the

sensory qualities from ordinary material objects like the rose. It is an application of the traditional argument from hallucination for the

indirect realist theory of perception.

The character of someone’s experience of looking at a red rose might be

the same whether there is really a red rose out there or instead the person is

just hallucinating. Hence, the argument

concludes, what the perceiver is directly

aware of in each case is really just something going on in the mind rather than

in mind-independent reality (even if it is caused

by something really out there in mind-independent reality).

Now, at one

time I accepted this sort of argument myself (and, like Goff, was influenced in

this connection by Howard Robinson, a philosopher whose work I too have long

admired and profited from). But I later

changed my mind. There’s a lot that can

be said about the topic, and I address it in Aristotle’s

Revenge (see pp. 106-113 and 340-351). For present purposes I will simply note that

Goff’s conclusion is a non sequitur,

as (once again) it seems to me that he ought to realize given other things he

holds. For he seems to think that the

argument gives us grounds for denying that anything like the red we see when we

look at a rose is really out there in the rose itself. But this would not follow even if we accepted the argument from

hallucination as a proof of indirect realism.

After all, Goff himself allows that the rose itself really is out there.

He doesn’t think that (what he takes to be) the fact that we aren’t directly aware of the rose (but only of

the mind’s perceptual representation of the rose) casts any serious doubt on

the reality of the rose. So, why would

the claim that we aren’t directly aware of the rose’s redness show that we have reason to doubt that there is something

corresponding to it out there in

mind-independent reality, in the rose itself?

In short,

even if we buy indirect realism, the rose itself (by Goff’s own admission)

still exists in a mind-independent way.

And by the same token, for all Goff has shown, even if we buy indirect

realism, the redness of the rose, as

common sense understands redness, still exists in a mind-independent way. The argument from hallucination for indirect

realism thus turns out to be something of a red herring (pun not intended but

happily noted).

Finally,

Goff says:

[Feser] doesn’t in fact consider my

main argument for panpsychism, which is a simplicity-based argument. I have

argued that panpsychism is the most parsimonious theory able to account for

both the reality of consciousness and the data of third-person science.

End

quote. But actually, I did address this

argument, because part of the point of the criticisms I raised was precisely

that Goff’s position is not parsimonious. For one thing, as I emphasized in my original

post and reiterated above, the panpsychist solution is simply unnecessary, because the problem to which it is a purported

solution does not arise once we see – as Goff himself emphasizes! – that Galileo’s

mathematized conception of nature is a mere abstraction that in the nature of

the case cannot capture all of matter’s properties. As I noted in my original post, if you draw a

portrait of someone in pen and ink, no one thinks that the absence from the black

and white line drawing of many of the features that exist in the person (color,

three-dimensionality, etc.) generates some deep metaphysical problem. It merely reflects the limitations of the

mode of representation, that’s all. But

in the same way, the absence of sensory qualities from physics’ mathematical

mode of representation doesn’t pose any deep metaphysical problem either. It simply reflects the limits of mathematical

representation, that’s all.

Hence Goff is

like someone who looks at a black and white line drawing, notes that it leaves

out many features, and then starts spinning complex metaphysical theories to “explain”

the “mystery.” In both cases, there is no genuine mystery and the problem

is completely bogus. And a theory

can hardly be “parsimonious” if the problem it claims to solve is a pseudo-problem. (Go back to my other analogy from above. Suppose I say “Let’s kill Bob, but then find

a way to bring him back to life!” And

suppose you answer “How about just not killing him?” Whose plan is more

parsimonious?)

For another

thing, and as I also pointed out in my earlier post, panpsychism creates new

problems of its own. As common sense and

Aristotelianism alike emphasize, conscious experience in the uncontroversial

cases is closely linked to the presence of specialized sense organs, appetites

or inner drives, and consequent locomotion or bodily movement in relation to the

things experienced. It is because human

beings, dogs, cats, bears, birds, lizards, etc. possess these features that few

people doubt that they are all conscious.

And it is because trees, grass, stones, water, etc. lack these features that few people believe they are conscious.

The point is

in part epistemological, but also metaphysical.

Aristotelians argue that there is no point

to sentience in entities devoid of appetite and locomotion, so that (since

nature does nothing in vain) we can conclude that such entities lack sentience. Some philosophers (such as Wittgensteinians)

would argue that it is not even intelligible

to posit consciousness in the absence of appropriate behavioral criteria. Naturally, all of this is controversial. But the point is that a theory that claims

that electrons and the like are conscious faces obvious and grave metaphysical

and epistemological hurdles, and thus can hardly claim parsimony, of all things, as the chief consideration in its favor!

So, Goff’s defense fails – and again, most of the problems are of Goff’s own making, because they have to do with parts of his position being inadvertently undermined by other parts. His exposure of the limits of Galileo’s mathematization of nature, his rejection of reductionism, his affirmation of external world realism, his call for parsimony – all of these elements of Goff’s position are admirable and welcome. But when their implications are consistently worked out, they lead away from panpsychism, not toward it.

Hi Dr. Feser,

ReplyDeleteOn at least some naive readings, Leibniz’s monadology appears to be a form of panpsychism, albeit a much more sophisticated panpsychism than what contemporary analytics such as Goff offer. You have described Leibniz as “the greatest of the moderns.” How does a monad-based panpsychism fare in your eyes?

As I recall, he answered this in the 2nd dialogue with Oppy when he described the theory as "brilliant, but nuts."

DeleteDear Mr. Feser,

ReplyDeleteas you say, panpsychists understand panpsychism as a solution to a metaphysical problem.

And as you have nicely shown, this "problem" is a pseudo-problem, an illusory problem.

I think the panpsychists do not understand what the real and actual metaphysical problem is for them, for which panpsychism is a solution.

The real problem for them and the real motivation for or behind their theory is how to explain the appearance of consciousness in natural history and in the individual development of the animal in the face of a godless, material world.

For without God, the appearance of consciousness in an unconscious material world is a true miracle. And miracles can be explained better with God.

Or consciousness lies virtually or potentially hidden in matter, but then we have a kind of design which needs a designer.

But if one makes matter conscious in all its forms, as panpsychism does, then God indeed becomes superfluous.

So panpsychism at its deepest core is a strategy to get rid of God. Philip Goff may not be aware of this core.

Greetings from Germany.

As a small confirmation of my thesis that atheism and panpsychism go hand in hand or are closely linked:

DeletePhilip Goff himself says that his panpsychism is strongly inspired by Bertrand Russell.

And one of Philip Goff's intellectual "teachers", namely Galen Strawson, says that Nietzsche is to be interpreted as a panpsychist:

"Here, I propose, we have the core of Nietzsche’s metaphysics."

"[10] reality is suffused with—if it does not consist of mentality in some form or sense." (Nietzsche’s Metaphysics? by Galen Strawson)

Bertrand Russell and Friedrich Nietzsche are among the greatest atheists in intellectual history. And it is no coincidence that they have inclinations and sympathies towards panpsychist ideas.

So how do you become a panpsychist. One is first an atheist and a materialist and a physicalist. This is the modern default position. Then, however, the occurrence of consciousness cannot be reconciled properly with that position. So the logically consistent physicalist must let the physical get permeated with the mental.

I wouldn't quite go as far as Anonymous but I think he's close. I don't think it's a conscious (or subconscious) attempt to get rid of God. "God" has already gone from their consciousness. They're in a mindset where physicalism "seems" valid and as Professor Feser quite rightly states, they then have to twist themselves up in knots to solve a pseudo problem (whether the hard problem of consciousness or hard problem of "qualities").

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, I'm rather confused by the assertion that some sort of "use" for consciousness must be present, and the idea that given its absence, this is some sort of "proof" of the absence of consciousness. You can then slip in God as an explanation for the emergence of consciousness, but this does not seem to do God justice.

I don't think it's merely in Indian philosophy that we come across the idea of the all pervading nature of consciousness (but we need to be careful here - we're talking about Chit-Shati here, dynamic, Conscious-Force, not the superficial chitta of mental consciousness.

I don't know the Christian mystical tradition as well, and I'm assuming Dr. Hart is persona non grata here given his lively defense of socialism. However, I would think we could grant him some insight into at least Orthodox Christianity ,and his characterization of the universally found "qualities" of God as "Existence Consciousness Bliss" at least suggests that what we call "matter" is merely a form of involved Consciousness.

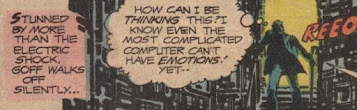

Sorry if this is off topic but how do you manage to find the perfect comic book strip for all your posts? Its truly an amazing feat!

ReplyDeleteThe biggest issue I see with panpsychism (as Ed noted in the previous post) is that it doesn't solve anything even if you grant it.

ReplyDeleteLet's suppose that every subatomic particle is in fact conscious as Goff postulates. Now, these particles have no sense organs, so they aren't actually conscious OF anything, and their consciousness doesn't affect their behavior, which remains mechanistic.

This offers precisely zero insight into how aggregates of these mechanistic but conscious (of nothing) particles could possibly "add up" to animals with a unitary consciousness that DOES affect their behavior and is integrated with their sense organs. This idea remains every bit and puzzling and nonsensical as such creatures being mere aggregates of mechanistic particles that aren't conscious.

A panpsychist might respond by rejecting reductionism, and say that conscious animals are NOT mere aggregates of mechanistic particles, but rather substances with powers of their own that are irreducible to the aggregate behavior of their parts. But this answer (which is correct) explains things equally well without panpsychism. Attributing consciousness to individual particles is just superfluous either way.

I suspect that what motivates this is an aversion to a theistic account of our origins. If consciousness is a real power of animals, but absent from all other matter, the conclusion is pretty nearly inescapable that is must have come into existence deliberately (eg by God guiding evolution to it from the start).

I think there's a hope that if we start with "a little bit of consciousness" in particles (and don't think about the details too rigorously), maybe it could somehow "add up" to animal consciousness in a bottom-up, unintended way given enough time. This doesn't work, the theistic implication remains when you consider that attributing consciousness to particles is superfluous, but I suspect that's the motivation.

So I'm actually somewhat sympathetic to panpsychism. As a Catholic, I don't actually believe it, and I will admit that I haven't fully fleshed out the details of my views.

ReplyDeleteHowever, I think it could be a very powerful position, and Feser is strongly underestimating it.

First, I will explain what I interpret panpsychism to be. Since the rise of computers, a relationship between entropy in thermodynamics and in information has been noticed. The storage of information reduces the entropy of the universe, and thus, requires energy. The more information something has, the more energy is required to store that information.

IMPORTANTLY, this energy refers to the information itself and NOT merely energy expended by sense organs to obtain that energy.

In other words, information can be though of as a physical quantity.

Consciousness (as I think it could be interpreted by panpsychists) is simply the possession of any information in a physical system that can be measured through a reduction of entropy.

Now, to critique Feser's article:

> It starts out accepting the view that sensory qualities aren’t really there in matter. But then, noting the problems this raises, it proposes that the solution is to hold that sensory qualities… really are there in matter after all!

This is, IMHO, not the strongest version of Goff's view. The sensory qualities are not in matter considered as pure extension (as, say, Descartes would consider matter). However, what Goff and panpsychists are saying is that matter is more than just pure extension.

What that "more" is, is the informational content of the matter, which is related to the spatial, "pure extension" aspect of matter though entropy and the energy used to reduce that entropy to produce that information.

To put it another way, it might be claimed that everything in the universe can be described by a certain number of bits. That bit content, just IS consciousness. We have a higher level of consciousness which accounts for our unique powers, simply because our brain has a higher number of bits than a rock.

Not saying I believe it. I just think, after reading about things like It from Bit theory, Shannon entropy, and Maxwell's demon, that it is a very strong direction for a physicalist to go in.

Just want to add that I think its a powerful direction for a physicalist to take because we KNOW from physical experiments that energy and information are interconvertible.

ReplyDeletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_in_thermodynamics_and_information_theory#Information_is_physical

So any fully fleshed out theory of panpsychism that is based on consciousness as information content, would (maybe) have empirical evidence to back up their metaphysics.

There is a Universal Conscious Force That Is Indivisible, Acausal, and Absolute. And everything including so called matter is spontaneously arising as an apparent modification of That.

ReplyDeleteThere is only Consciousness, and Light which is the energy of Consciousness.

I suppose that if you want to deny the immortality of the soul, denying its indivisibility might be a good place to start. It seems to me that this is one thing that panpsychism does.

ReplyDeleteBeing fair to the average panpsychist, i don't think they usually even consider viable that a thing so "complex" like our minds could be anything more that a colection of tiny little pieces. The reductionist mindset is very popular and if you have it it is hard to see things diferently.

DeleteDefinitely you should read this article which resolves the controversy between Goff and you, Mr Feser:

ReplyDeletehttps://surimposium.rhumatopratique.com/en/explain-consciousness-as-phenomene/

"This is comparable to thinking about killing someone, and then, noting how problematic this would be, proposing that after the murder we look for some way to resuscitate the corpse, Frankenstein-style."

ReplyDeleteLoved that analogy. I'm going to save it for other occasions.

This is the opposite of an argument. The most common fate of ideas is to die and resurrect in a slightly different form.

DeleteI loved Goff answer. Not only he is smart and kind but he is very direct. "Here are my arguments, there you go".

ReplyDeleteBut you touched on a very interesting point with the sense organs thing, Dr. Feser. It reminds me of a problem i have both with panpsychists and with people like the advaitists: what exactly is a consciousness that is not conscious of anything? I just don't see how any kinda of mental activist with no object is even a coherent concept, for to be conscious one need awareness, and this necessitates something to be aware of.

Is God conscious?

Delete(Sorry for the lateness, Jaime)

DeleteIs God conscious? It depends.

Is God conscious on the sense of having the sensual experiences of seeing, hearing etc something? The sort we share with other animals. Nope, i don't see how could a immaterial being have one.

Is God conscious on the more broadly sense of having knowledge of beings? Yes, there is on Him something analogous to intellect and He knows Himself directly and everything else by knowing how He could share His being by creating limited beings.

(Notice than this all uses thomistic language)

As a trinitarian, i don't think that God intellect is capable of not having a object, for He aways know Himself, so i don't think i understand the question.

Galileo's error was Galileo Figaro magnifico-o-o...

ReplyDeleteHi Ed,

ReplyDeleteWhile you are correct in arguing that panpsychism is ontologically unparsimonious, there are two major problems with the naive Aristotelian view that sensory qualities inhere in ordinary material objects.

First, it imputes ontologically singular properties to material objects. In addition to its numerous third-person properties, a rose has the first-person property of being able to cause people to see red. (This property might itself be caused by some other properties of the rose, but that is neither here nor there.) The point is that the naive A-T view rules out the possibility of identifying a single defining attribute of the rose (say, its cellular structure) which explains all of its other attributes. On the A-T view, the best we can do is catalogue the various attributes of a rose and put them under the umbrella of its substantial form. Scientists, however, want to do more than that. They want to be able to deduce all of these attributes from a more fundamental attribute. (In practice this is very hard to do, but that's the goal of science.) The problem is that there's no way to deduce a first-person property from a third-person attribute.

Second, it is forced to impute a host of these peculiar first-person properties to ordinary objects like roses. The way a dog sees a rose is quite different from the way I see it. So it seems that the rose has one set of first-person properties relative to humans and another set relative to dogs. Someone suggested in a previous post that maybe humans simply extract more information about the rose with their eyes than dogs do with theirs, and that there's no need to impute multiple sets of first-person properties to roses. Aside from the fact that you can't put humans, dogs and other animals on a sliding scale of the visual information they extract from things they see (as it turns out there are multiple dimensions - dogs are worse at seeing color, but better at seeing contrasts), the key problem with this suggestion is that it reduces a first-person property (being able to cause the experience of color) to a third-person one (possessing visual information), which is precisely the kind of move that naive A-T rejects.

Readers can find more on animal vision here: https://crosstalk.cell.com/blog/5-things-you-didnt-know-about-how-animals-see-color

My own, more parsimonious view is that the first-person property of color only exists in complex living bodies (such as animals with the right kinds of brains) and that the only bodies that possess both first-person and third-person properties are animals with minds. What roses have is a (third-person) tendency to stimulate rods and cones, which is grounded in their cellular structure. That makes more sense, in my opinion. Cheers.

@Vincent Torley:

DeleteThe way a dog sees a rose is quite different from the way I see it.

That's something you can not know. It seems to me that you are projecting your world-'view' (pun intended) upon the animal kingdom.

And I really appreciate your work at Dembski's blog and your fight against the curse of materialism, but I think that this time you are wrong :)

That seems correct. The naive color realism we see normally seems to me quite cool, except in a more sophisticated way. Color is there.

ReplyDelete"But we see colors this way and other animais this other way"

Exactly like they do with objects size, format etc. Berkeley pointed that out before, bro.

Gone is the twin fantasy of res cogitantes and res extensae! The redness of a rose, it turns out, is not after all what Galileo conceived to be a “secondary” quality, a mental apparition mistakenly projected upon a colorless external entity. Following four centuries of utter confusion, it turns out that roses are indeed red, and that the “simpletons” have proved to be wiser than the pundits of the Enlightenment, who to this day have failed to realize that they are living in a fantasy world — or, better said, would be if they actually believed what they affirm...

ReplyDelete'Do-We-Perceive-The-Corporeal-World'?

https://philos-sophia.org/perceive-corporeal-world/

There's an ontological chasm between the firing of neurons and the seeing of a red rose. A chasm that can be bridged and mended together by a Sagyrite who lived 2500+ years ago, a Dominican friar who lived 700+ years ago and a philosophy professor who 'animates' (pun intended) the 'blogosphere' today.

R.I.P., René.

*Stagirite*. Welcome back, Aristotle. The 'modern' mind is in dire need of your teachings. Look at the mess we're in. Lol.

DeleteImagine a creature (an alien perhaps) who could see ultra-violet light. Perhaps they see this color as a shade we can’t imagine (which I find unlikely) or perhaps their ability to see a wider breadth of the light spectrum shifts their entire sense of color perception in unpredictable ways, making red roses look like what we would yellow. Would this creature really be mistaken about the correctness of their phenomenal judgements because they differ from ours. Perhaps they’d be MORE correct than we are, given that they see a larger visible spectrum than us. When it comes to “secondary qualities” it’s hard not to see the perceiver as constructing something (phenomenonlogical representation) which isn’t in any external object, except of course, as a potential to cause such representation in minds which can “decode” the object a certain way, determined by the perceiver’s cognitive system.

ReplyDelete@ Anonymous:

DeleteImagine a creature (an alien perhaps) who could see ultra-violet light.

Sorry. I did not see this reply up until yesterday.

This a crucial question: how could I imagine what an alien sees? We humans can not agree about the many shadows of red or blue or green that there are, so how could I imagine something that in principle can not be done (about an hypothetical alien's visual perception?)

In short, even if we buy indirect realism

ReplyDeleteBut we aquinians do not buy indirect realism, because it is contrary to reason. The Saint would have not given these people the time of day. The only realism posible is that of adequatio rei et intellectu. And the future of our civilization hinges upon this distinction.